By Emmanuel Olawale, Esq.

The Olawale Law Firm

In the midst of the recession, the Tuesday after the Memorial Day weekend in 2009, in my fourth year as an attorney, I finally realized my dream of starting and running my own practice, The Olawale Law Firm was born. It was birthed when most law firms were cutting staff, when some big law firms were dissolving long-held partnerships, while new lawyers were competing for jobs that were non-existent and during a time when the aura surrounding solo practice or start-up practice was of doom and gloom.

It was the right and appointed time, even though my wife was enrolled in graduate school fulltime and not working outside the home, and I didn’t have funds saved up, startup loans from any source, an inheritance or home equity to cushion my entry into private practice. I was confident, nonetheless, that it was the right time. I was determined to use the resources I had, plant the seeds in my hands with the hope that they would germinate and reproduce in plentiful multiples. I knew it was the right time to realize the American Dream of owning my own business, become an entrepreneur and contribute to the American economy as a business owner.

The thought of failure didn’t once cross my mind. I had first conquered my mental mountain before embarking on the physical mountain, because it’s not possible to surmount the physical mountain without first conquering the mental mountain. The mind is the wellspring that waters the seeds of ideas to success.

I started seeing clients at my home office and meeting some at cafes, libraries and bookstores. I saw several clients this way for three months and was able to meet the household financial needs as well as raise enough capital to pay for an office outside the home.

I didn’t specialize in any particular field; I took any case that walked through the door. I took on criminal, immigration, personal injury, contract review, contract drafting, business, divorce, child custody, juvenile cases and tax and real estate matters. I did not discriminate against cases if a client had a problem. I specialized in the client’s problem and provided the solution.

After three months, I still couldn’t afford a permanent office space, so I took advantage of the virtual office option. With a virtual office, you aren’t always at the office physically. You only pay for a particular number of hours to use the facility. A receptionist there answers your calls and transfers the calls to your cell phone as if you were always present in the office. You have a permanent office address and mailbox to receive mail. When clients come, they are welcomed at a fabulously furnished reception area by pleasant receptionists and offered coffee or tea while they wait.

I selected a location that would be accessible and acceptable to everyone. I chose a class “A” office that would represent excellence, distinction and professionalism. My intention was to appeal to people of all races and classes. I didn’t want to be boxed into a corner or location that only catered to minorities and Africans. I wanted my potential white clients to feel as comfortable as my black clients, my Hispanic clients to feel as welcome as my Asian clients.

In the beginning, I signed up for sixteen hours a month. But I soon discovered within the first month that the hours weren’t sufficient, as my client list increased and the traffic and calls for my services quadrupled—so I negotiated additional office hours.

After availing myself of the virtual office style of practice for six months, I was ready and financially able to rent an office space. So, I signed a lease.

In the course of my practice, I have, through divine favor, been able to resolve cases that many lawyers had rejected, help many clients who were told that their cases were impossible. I see the profession of law as a calling, a ministry. I see myself as an officer of the court and a minister of the law. I see my practice as an avenue to build lives; to edify; to admonish; and to revivify the defeated, the deflated and the marginalized. It is like the calling to priesthood or to a religious ministry. While priests use religious books as tools to advance their ministrations, as a lawyer, I believe in the use of the law as the tool to propagate change, to advocate and redeem, to construct, to seek justice and to positively impact lives.

A probate judge once told me in open court, “I’ve been practicing for over 30 years. I hope you spend more time practicing because I have not before seen a lawyer display so much compassion on behalf of a client. It is one thing to serve and make a living, it is another to serve and touch lives.” To my clients, he said, “You have the best lawyer, who has done a wonderful job for you. I hope you know this, because no lawyer out there would do what this man has done for you for this fee.”

This judge said this on the record at a wrongful death settlement approval hearing stemming from the death of a two–year-old girl, who was killed by a reckless teenage driver.

As one can imagine, the parents were so distraught and inconsolable even almost two years after the fatal accident. When I met with the parents to take on their case, I felt the irreplaceable loss they had suffered. I was overwhelmed by their grief. I felt inexplicable empathy and realized that no matter how much money they were to be paid for the death of their toddler, it wouldn’t heal their grief or fill the deep hole of bereavement indelibly scarred into their hearts. No amount of money could substitute for the smile of that little innocent child or compensate for the promising years cut short by death. As such, I decided to charge them a fraction of the prevailing attorney’s fee; I discounted my fees by 70 percent. This act of professional altruism was what moved the judge to effusively thank, encourage and praise my act of service.

Then, when the settlement money almost created a wedge between the couple, I had to sit both of them down and counsel them. I had to make them realize that the fight over the money would tarnish the memory of their dead child. I was able to reunite them and made both of them understand that the money might attempt to compensate for their losses, but it wouldn’t bring back their lost offspring and that their grief was best alleviated when shared and experienced together.

I often feel the gratification of service when I represent indigent clients for free or for ridiculously minuscule fees and yet advocate on their behalf as if I had been paid millions. In the end, these clients are eternally grateful and I see the positive difference my act of service made in their lives.

I remember the case of a young woman whose employment was unjustly terminated by the manager of a retail store on some discriminatory grounds. After the termination, the store refused to pay her for the last week of employment for over three weeks. The same week of my involvement, I was able to get the employer to overnight the check.

At the mediation of the matter a few weeks later, I got the manager to admit her wrongdoing and apologize to my client face to face. I got the employer to rehire my client in a better position with better pay and to pay her for the time she was unemployed as a result of the wrongful termination. All this I did without charging my client a dime because I knew she couldn’t afford the fees, but needed an advocate to get her justice.

I recall the case of another client who had been held in jail for over two weeks without representation. I took on his case for free, visited him in jail, negotiated to get three out of the four criminal charges against him dismissed with no additional jail time and got him set free without collecting a dime. Although he and his family had no money to pay for my services, their flattering adulation and their relentless referrals testify to the depth of their appreciation.

As a lawyer of African descent, trained in the United States, I act as a cultural buffer, a cultural translator, a bridge between my client and mainstream America. I understand the immigrant culture and the African-American as well as the majority culture. Most issues that most attorneys within the majority culture don’t understand, I understand, and my clients trust me enough to discuss them with me. Most issues foreign to white judges and lawyers, immigration officers and other agents are native to me. As such, I use my intercultural experience as a viaduct between these cultures to the benefit of my clients.

I took on the case of an African immigrant in his fifties who came to me with his wife after unsuccessfully trying to obtain permanent residence for years. The man came into the U.S. legally with a valid visa in the year 2000; however, over the course of time, he overstayed and his visa expired. He later married a U.S. citizen and they had two children as fruit of the marriage. However, the marriage fell apart and so did the immigration petition and applications filed on behalf of the man. As a result, the United States Citizen and Immigration Service (USCIS) began deportation proceedings in January 2007.

About a year into his immigration dilemma, the client reunited with his high school sweetheart, who had recently become a widow. He became her source of comfort and lent his ears to her lamentations and grief. Meanwhile, he was still in the U.S. while the woman, a U.S. citizen, moved back to her home country of Ghana. She did this after the death of her husband in order to wind up his affairs and complete some projects she and her deceased husband were working on before his death.

After

maintaining constant telephone contact for over a year, the high school

sweethearts decided to get married. The woman flew in from Ghana to tie the

knot with her newfound partner. They married in a quiet ceremony. As a result

of this nuptial, the woman knowingly gave up the monthly Social Security

financial benefits she had been receiving stemming from the death of her

previous husband. Nevertheless, this was a small price she was willing to pay

to capture love and companionship once again.

Subsequently, she filed a

petition for her new husband so that he could obtain a green card. The USCIS,

the immigration arm that deals with such matters, approved the petition after

having being satisfied that the marriage was genuine and not entered for

immigration purposes.

Nevertheless, because she was working on completing a hotel building in Africa that her prior husband started but didn’t complete before his death, she couldn’t fully relocate to the U.S. until she had concluded the project. In spite of the diametrically opposed obligations she had to handle on two different continents, she traveled to the U.S. to visit her husband three to four times a year.

After the approval of the marriage petition, her husband applied for his green card before the immigration judge. However, the Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) assistant chief counsel opposed the application and requested a hearing so that the couple could prove to the court again that their marriage was genuine even though USCIS had already come to that conclusion. The hearing was held and the immigration judge concluded that the couple’s marriage was genuine, so he scheduled another hearing to determine whether or not the husband was eligible for permanent residency (green card status).

About a week before the green card hearing, the couple consulted with me for representation because their prior counsel couldn’t continue to represent them for personal reasons unrelated to their case.

In July 2009, we appeared for the hearing. The man, who was the intending immigrant, was put on the stand and grilled for hours by ICE’s counsel until it was time for the court to close. As such, we weren’t able to put the wife, who flew in from Ghana for the hearing, on the stand. In short, the hearing could not be completed on that day because of the lengthy cross-examination of the husband by the government’s counsel. Hence, the judge adjourned the hearing to September 30, 2009.

The wife had to return to Africa shortly after the hearing. However, about a week prior to the September hearing, she flew back to join her husband, and presented herself for the trial. Just as the husband was treated during the hearing in July, she was subjected to a lengthy, long-winded cross-examination by the government’s counsel.

Government’s counsel asked her why she hadn’t moved back fully to the U.S. and she explained the nature of the projects she was handling and how she couldn’t just leave without finalizing the project as her deceased husband’s family was waging a battle to dispossess her of her deceased husband’s properties. The opposing counsel then suggested that if my client couldn’t move here until she stabilized her inheritance, why couldn’t her new husband move to Africa to join and live with her? My client replied that she and her new husband had both decided to stay in the U.S. especially since she was a U.S. citizen and that she was planning to finally move back by the end of 2009.

On redirect examination, I asked my client to explain to the court how it would be perceived in the African culture if a man moved in to live with his wife. She told the court that it would be seen as a disgraceful act of a man without dignity. I followed up and asked her to explain to the court how the culture in her country would react to a situation in which her new husband moved in to reside with her in the house that was built by her deceased husband. She elucidated that such an act would be under the highest taboo and could lead to her eviction from the house by her late husband’s family, especially since they already were engaged in an ongoing legal dispute regarding the property.

I was able to elicit these responses from her because I understand the African culture and what often happens after the death of a relative, especially the death of a man in his prime. I knew that she was probably going through battles with her former husband’s family over property, even though she hadn’t told me this. I also knew that she would likely have been accused by her in-laws of killing her husband as this is common in most African culture when a man dies young.

At the end of the trial, the immigration judge granted my client’s application for adjustment of status (giving him the green card status). He further found that all the witnesses were “substantially credible.”

In spite of the judge’s well-founded decision, the government counsel, looking thunderstruck, appealed the decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) because she, being primarily acculturated in the United States, couldn’t understand how two people could be married, yet one is staying a continent away, an occurrence very common within the immigrant community. The counsel couldn’t understand why the woman didn’t just round up her affairs back in Ghana and move to the United States to join her husband. She couldn’t understand why the new husband didn’t move in and live with his wife at her house in Ghana. She was culturally ignorant of my client’s situation.

The government’s counsel, knowing that her appeal had no factual and legal basis, embarked on a backdoor way to deny my clients their rights by contacting the local immigration field office to retroactively deny the marriage petition, which had been approved over a year previously.

The local office, in turn, issued a Notice of Intent to Revoke that would nullify the prior approval to my clients. I vehemently opposed the issuance of the notice, but responded under protest, producing all the documents they requested and more. I also wrote a personal letter of complaint to the field office director and her supervisor, explaining that the process of retroactive revocation being used against my client violated due process of law, was unjust and shouldn’t be condoned, and that the agency shouldn’t allow it to be used as an instrument of injustice by a sister agency just because a government counsel was dyspeptic about a judge’s decision.

In spite of the overwhelming additional evidence my clients submitted, the local immigration office revoked the visa without any credible or reasonable basis. The regional office director also wrote me back sanctioning the actions of the field office citing that it was not a violation of due process. Hence, I appealed this unfair decision to the BIA.

Meanwhile, I also sent a letter of complaint to the chief counsel about the assistant chief counsel, charging that his assistant was abusing her authority through her actions and the quest to ensure that an unjust decision was reached, contrary to the judge’s decision after lengthy hearings and trials. I asked him to stop the unjust process and call his assistant to order and to ensure that similar situations did not arise in the future.

The chief counsel called me back a few days later, acknowledging my concern, but said that he believed his assistant’s actions were within the province of their power.

I fired back a letter to him expressing my disappointment with his decision in spite of the apparent injustice and abuse of power. I decried his support of his assistant and promised that I would not stop short until justice prevailed and said that “I will assiduously assert the rectitude of the matter.”

After the revocation of my client’s approval, the assistant chief counsel filed a Motion to Remand with the BIA, stressing that my client’s visa had been revoked by the USCIS and that the BIA should send the case back to the judge to order my client’s removal from the U.S.

I countered the motion accordingly and explained the process through which my client’s visa was revoked in spite of the evidence he presented and the immigration judge’s decision. The BIA agreed with me and denied the government’s motion to remand.

In December 2010, the BIA made a decision on my clients’ appeal of the revocation of their visa approval. The BIA agreed with my arguments, ruled in my client’s favor and instructed the local field office to reinstate the visa approval immediately. A month later, January 2011, the BIA denied the appeal filed by the assistant chief counsel and held that the judge did not err in approving my client’s green card application.

Upon receipt of these decisions,

I sent a letter to the local immigration field office requesting that they

issue my client’s green card immediately. My client scheduled several

appointments with the USCIS to commence the issuance of his green card.

However, every time he appeared at the field office, they told him that they

had not received his file back from the office of chief counsel, which was only

two hours’ drive away. They promised to request the file, only for my client to

go back the next time and be told that they did not have his file.

I gave them sufficient time

to ensure that enough patience had been exhausted. When my client hadn’t

received his green card by the middle of September 2011, I sent a letter

requesting the local field office issue the green card and adhere to the

judge’s decision, especially since about two years had passed. I also pointed

out that it could not have taken over five months to transport a file from a

city two hours away, even by road.

The following week, my client received his green card. The process had taken over four years, during two of which my client was in immigration limbo, fighting the injustice of the system and the powers that be. Although in the beginning it seemed that my client was entangled in an ineluctable legal net fashioned by government agents, the people with the power, he eventually prevailed because he had an advocate who would not relent until justice was served.

This was a case that ignited the burning embers of constructive, justified anger within me. My anger was based on compassion and grieved by injustice. I delved into the quest for justice without fear and with an intrepid determination to get my clients justice even if they couldn’t afford it, since, in this case, they couldn’t afford to pay my reasonable, prevailing fees as the matter was dragging on for years. Nevertheless, I wasn’t discouraged by the lack of funding, but was propelled by my vision to be a voice for the voiceless.

In the face of unfairness perpetrated by the people hired by the government and sworn to enforce the law, I made it a duty to oppose the injustice to the highest level possible. Though justice was delayed, I ensured that it was not denied regardless of the roaring powerful opposition mounted by two separate immigration agencies and their officers. The same spirit of determination that possessed me as a child when my parents refused to allow me to travel with the band manifested itself in this case and pushed me to face and challenge every obstacle and person in the path of justice. My anger led to a positive result. It was for situations such as this that I became a lawyer.

I recall a child custody case I handled in 2009, the instance of a father who was wrongly accused of abandoning his two young children after their mother died of cancer while the children were in her custody. The county’s children’s services as well as the family of the deceased colluded to ensure that this man would permanently lose custody of his children. They fabricated stories of abuse—physical and sexual—against the father, and they accused him of intentionally abandoning his children while the mother was stricken with a terminal illness, when in fact, he was never made aware of the nature of her illness or the seriousness of her ailment because he lived in Florida.

The case was brought in Coshocton County, Ohio, a very small county of about 36,000 people that was 93.7 percent white, 1.09 percent black. My client was a white man, who was referred to me by his sister. He and his sister from Michigan saw beyond my race and accented American English and trusted me to handle the case skillfully.

By the time he consulted with me, my client had been denied custody and frequent access to his children for over three months while the children were placed in the custody of their maternal aunt. It was a shock when I appeared at a scheduled hearing because my client was never expected to fight back. They simply believed he couldn’t afford representation as he had showed up on two prior occasions without a lawyer.

My investigation and discovery requests later revealed that the basis upon which my client was being denied access and custody to his children was nothing but fabrication. I challenged the County Children’s Services investigation and handling of the case and filed motions to speed up the case as the case was being delayed by the County’s Children’s Services in collusion with the clerks—as everyone knew everyone and I was the only “outsider,” coming from Columbus to raise hell.

I pressured the maternal aunt, who was awarded custody of the children through her attorney and squeezed the legal jugular of the County’s Children’s Services through my legal briefs until they caved in and dismissed the neglect, abuse and abandonment case against my client.

I clearly remember the smile on the client’s face as the court delivered the good news, acknowledging that he was on the right side of the law and that he deserved to see his children and to have them in his custody after being kept away from them for over six months. His countenance of thanksgiving, his sister’s effusive gratitude and his brother’s generous display of appreciation were much more than any fees they could have paid.

After the children were handed over to my client, my client later informed me that the maternal aunt told him that her attorney and the Children’s Services attorney said that they couldn’t hold on to the children or sustain the neglect, abuse and abandonment charges against my client because my client hired “a big-shot attorney from Columbus,” who came there to “raise hell.” I took the comment as a compliment as I didn’t seek to compete against the system or against the majority; it was my intention to practice within the highest level of professionalism and to meet the professional standard set for all.

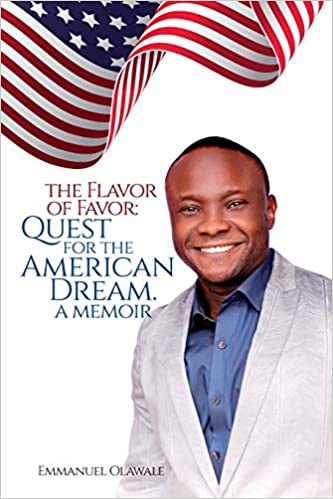

(Excerpts from The Flavor of Favor: Quest for the American Dream – https://www.amazon.com/Flavor-Favor-Quest-American-Dream/dp/1514242540